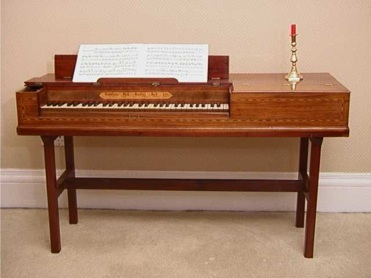

1:Square pianos like the one shown here first appeared in London in 1766, and were an immediate success.

Their distinctive sound and almost indestructible mechanism made them very popular with harpsichord players — and their novelty created a new fashion almost overnight. Famous composers of the era who used such instruments include J.C.Bach and J.C.F.Bach, Gluck, Paisiello, Cimarosa, and Clementi, not to mention music historian Charles Burney, who bought several. But their most influential fans were women such as Queen Charlotte of England and Marie Antoinette of France. Both were fond of music and, like many of their contemporaries, they were charmed by the tone of these pianos, not simply in solo pieces but in ensemble, and most importantly, in accompaniments for songs. Russian Empress Catherine the Great owned several English square pianos, of which her favourite was reportedly one by Zumpe & Buntebart fitted with organ stops in a cabinet beneath, coupled so that both instruments were heard at the same time.

The most prestigious makers in the pre-1780 period were Johannes Zumpe and Gabriel Buntebart, Adam Beyer, John Pohlman and Frederick Beck. Shown above is an example by Beck, inscribed, Fredericus Beck Londini fecit 1775, restored by Michael Cole.

Several varieties of tone can be found by use of three hand-operated stops in the compartment at the left of the keyboard. The first stop lifts the treble dampers (from middle C upwards); the second stop lifts the bass dampers; and the third presses buff leather against the end of each string so as to imitate the sound of a gut-strung harp.

These were by far the most popular pianos throughout Europe during the eighteenth century. Hundreds of examples survive — in France, Spain, Belgium, Holland, Germany and Switzerland. They were equally popular in Sweden and St Petersburg — and in North America. Some were fitted with pedals (the earliest known is dated 1774) either to work the stops already mentioned, or as additions that opened part of the lid (the so-called 'swell' making greater contrasts of piano and forte). Another, much rarer pedal, sometimes fitted by Beyer and Pohlman, moved the keyboard to sound a delicate una corda, activating one string of each unison pair.

Although many makers continued with this basic design up to 1810, significant improvements were introduced by a number of important makers during the 1780s and 1790s. Principally these focused on making the touch more expressive by including an escapement mechanism, and concurrently, an upward extension of the compass from five to five-and-a-half octaves. Leading makers in London at this time were Longman & Broderip, brothers Frederick & Christian Schoene, and John Broadwood, and in Paris, Sebastien Erard. All were subsequently eclipsed by the pianos bearing the name of Muzio Clementi who gave up his concert career to rescue the Longman & Broderip firm after its collapse in 1796 – relaunched under the name of Longman, Clementi & Co. Later he took a bigger, controlling stake, when the firm was renamed 'Muzio Clementi & Co' in 1801.

2:Shown here is a typical square piano of 1815, this one by William Stodart, London.

It has the typical five-and-a-half octaves, and a damper pedal. Notice that the pedal is under the left foot, not the right. This was customary at that period with all makers, even though contemporary grand pianos had the sustaining pedal under the right foot. After 1800 most English square pianos had just this one pedal (for the sustaining tone), but German pianos, and many American ones, often had a second pedal for the soft-sounding 'moderator' effect. French square pianos were often supplied with a row of four pedals: dampers, harp, moderator and swell.

After 1820 square pianos were constantly redesigned for a more powerful tone. English square c.1820[MP3 file]. The keyboard was extended upwards again, to six octaves, and afterwards in both directions to reach seven octaves. To achieve this stronger tone string gauges were progressively increased, until the strain was almost four times greater than on eighteenth-century pianos. The hammers were made larger, and heavier, and in consequence the touch lost its former lightness and facility. In an effort to prevent structural collapse these later pianos were fitted with an iron hitch plate (from around 1825) and afterwards, on American pianos, full metal framing (from around 1840).

3:Shown here is the ultimate square piano, for sophistication and quality of workmanship.

It was made by Mathuschek & Co of New York, about 1875. It has a full iron frame, with over-stringing on three levels. The tone is very strong, almost equal to late nineteenth-century grand pianos. The elaborately carved casework, in a pseudo-baroque style, now has a polished ebonised finish, perhaps applied by an over-enthusiastic piano shop; many by this maker have rosewood veneered exteriors. In England and France the last square pianos were made about 1865. By then the modern style of compact uprights, called 'cottage pianos' or 'piccolo pianos' had become more popular for small rooms, though their touch was never as good as square pianos'. The last American squares were made c.1905. Thereafter square pianos, particularly the earlier examples, were regarded nostalgically as something quaint and old-fashioned, and many artists of genre scenes used them as props, played by a young lady in Regency-style dress, to evoke a bygone era.

Fortepianos & Squares

What exactly is a fortepiano? While there is no strict definition, the term has recently come to be used to refer to particularly early pianos and their replicas. Pianos called "fortepianos" are noticeably different from the relatively large and louder llate 19th and 20th century instruments most people comfortably recognize visually and aurally as pianos. Note that to confuse the issue, all pianos have been called "fortepianos" in some countries, and still are in some!

We have put into this category pianos notable for:

Their earliness. In generally, fortepianos date from the 1700's to the 1840's.

Their relative lack of metal and nearly complete reliance on wood for the structure. There may be a small bracing and a metal bar or two, but there will absolutely not be a cast iron frame.

Their relatively light stringing and small hammers when compared with later pianos. Indeed, the very early example resemble harpsichords in sound more than they resemble pianos to some!. Almost always, fortepiano hammers are covered with leather, giving a very clean precise sound.

We also include in this category replicas of or new instruments inspired by very early pianos.

Clementi square

Clementi was not only a famous performer, but a fine piano company manager.

c. 1825 - serial no. 24629 / 506

Early Square Pianos

I have placed my examples of early square pianos in the fortepiano category because they fit the criteria above beautifully, and because it is very important to NOT place them in the same bag as late 19th century square pianos. You will notice that we do not carry late 19th century square pianos. We choose to carry instruments which are a pleasure to own and that are good investments. I will say no more about large late 19th century square pianos.

Early square pianos were fabulously popular household instruments from the 1760's through the 1830's. Neither so space consuming nor expensive as grands and were a requirement for the homes of the growing merchant classes and the townhomes of the upper classes. Their sound is light and clean, perfectly suited to the parlor and perfect for accompanying the popular airs of the day or playing the sonatas of Haydn, J.C. Bach, or the other famous late 18th and early 19th century composers. Beethoven's arrangements of Scottish songs would undoubtedly have been popular volumes on the square pianos of London and the colonies of North America.

att. Ferdinand Hoffman, unsigned

ca. 1785

方形钢琴的制造过程:

|

A newly arrived stack of white spruce for new soundboards. The heavy pieces at the left of the stack will be used for soundboard ribs.

Both, Sitka Spruce and White Spruce are used in our shop, depending on the kind of project.

All soundboards are made from scratch by us after the wood has been dried to the lowest possible moisture content. |

Sitka Spruce boards are laid out over a thirteen year old ESTONIA concert grand, observing a 47 degree angle in relation to the straight side of the piano.

This piano was made by the Estonia firm during the period in which the country of Estonia was still part of the USSR. Materials and workmanship were not up to the best European standards of the time. Renovations and modifications have been made which make the instrument much more valuable and successful in every respect.

Here is a section of the new ESTONIA soundboard. Notice the new decal and also a newly installed multiple ply Eastern Maple pin block. The old one had only three plies and had already developed some cracks.

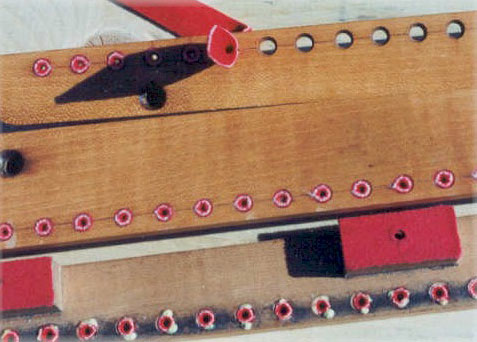

New bridge caps for the ESTONIA also. Here the bridges are being notched.

A newly made soundboard for a 1906 GAVEAU concert grand.

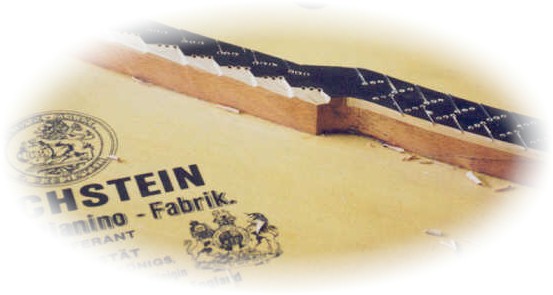

A newly made soundboard for an 1894 BECHSTEIN grand piano.

Notching the bridges for a 1894 BECHSTEIN grand piano

The bottom side of the soundboard of a circa 1785 HENRICUS HOLLAND Square piano. For antiques like these, it’s of the utmost importance to salvage the original parts of the piano. This soundboard was re-installed, but with new ribs.

Notice the odd shape of the ribs in comparison with modern ones.

Suspensions have been cut at the spot where they cross the bridge on the other side of the soundboard.

The new and old ribs for the HENRICUS HOLLAND square piano

Cabinet repair is often necessary. Here we see a new candle holder stand being copied from an existing one belonging to an 1801 WILLIAM ROLFE square piano.

When no examples are available, new ones have to be designed according the style of the period.

Making a new pinblock for an 1859 ERARD grand piano.

These pinblocks are mortised into the piano’s case. It is usually advisable to make a new pinblock section and install it on the rest of the existing pinblock, rather than cutting into the burled walnut piano case and removing the old pinblock.Here we see the new section being pre-fitted before it gets glued in place.

Clamping a new pinblock section in an 1859 ERARD grand piano.This pinblock section has to be very well bonded. Therefore many heavy-duty bar clamps need to be employed. Some heavy screws will be installed to ensure long term stability.

New bushing cloth being installed in the damper guide rail of a BECHSTEIN grand piano.

Since the cloth bushing wears out most at the front and back of the hole, it’s essential that the joint of the cloth is located at one of the sides of the hole where pressure is the least. This ensures a very long lasting bushing.

When in rare circumstances a key frame becomes warped and makes noise when played hard, it is best to make a new key frame. As with many other things which need to be made or copied for a given piano, this is precision work. This key frame belongs to a BECHSTEIN grand piano of 1887.

This Heintzman & Co. upright piano is ready to have a new sound board installed. Because this is a tall upright piano, its strings are about as long of those of a mid-seize grand piano.

Many pianists don't have room for a grand piano. A tall upright is then the solution when the same sound quality is desired.

Several times it happens that an incomplete early piano arrives in our shop. This can relate to action or furniture parts.

Such was the case of a 1854 Chickering square piano. The lyra and most of the wooden levers that operated by the pedals were missing, as was the moderator for the "soft" pedal.

It is not always possible that the same piano is at hand to see how the missing part(s) look like.The next step is then finding pictures.

A book on early pianos shows a "carbon" copy of this Chickering. It's in the Boston Museum Of Fine Arts.

Fortunately it was quite easy to copy the lyra. The proper dimensions were calculated. Then wood was glued and clamped together to cut the lyra from.

The pictures show the carvings on the lyra after it was cut to shape

Then ready to be finished to color match

.jpg)

The new levers for sustain pedal and soft pedal. In this case, a so called moderator which consist of a wooden strip with soft pieces of leather attached, is inserted between the hammers and strings if the pedal is pressed down.

This moderator can be seen on the fourth picture. It was missing also and had to be made by trial and error, but knowing how it should look.

The fifth picture shows the piano finished and playable.

|

|